Cutscenes, also known as full motion videos or interactive events, are some of the most important parts of storytelling in video games. They’re prominently featured in video games these days. Over the decades, the use of cutscenes has expanded from simple on screen text, to full animated movies with production budgets that can rival films.

But what really goes into making a cutscene? How much time does it take to develop the cutscenes in a game? How are they integrated? How has their use evolved over the years? Let’s take a closer look at the world of cinematic animation in video games.

The evolution of video games is quite amazing in itself when compared to the evolution of other industries, if you consider that we’ve gone from text adventures, all the way up to the HD systems we use today. Sounds impressive right? While all this has taken place in the short time frame of just a few decades, with each generation taking a giant leap in one form or another, cut scenes have perhaps taken the biggest leap in an even shorter period of time.

Cutscenes in their most basic form since the mid 70s were nothing more than a little character being moved across the screen and some text displaying the story. But this was fine, because it’s not like we expected much from shooting anything that wasn’t you, or rescuing the kidnapped Princesses from monkeys, right?

Example scene from Final Fantasy VII.

Disk based media obviously had the biggest impact on cutscenes; with some games going the live action route–often with poor production values, but sometimes becoming popular for that very reason alone. Other games took the route of pre-rendered or real time cutscenes. Final Fantasy VII onwards show great examples of pre rendered cutscenes, while the Uncharted games demonstrate real time cutscenes used effectively. Real time cutscenes have, however, evolved more from the evolving technology of games consoles, not the storage based media of the game itself; since they are shown in real time and are sometimes interactive.

You can group cutscenes into three categories; Live Action, Pre-Rendered and Real Time. We’ll look at the pros and cons of each, and I’ll also discuss how they can best be used–or not, in some cases. It’s worth nothing that cutscenes aren’t important to narritive, being more of a cinematic tool. You can provide a perfectly good narritive without resorting to cutscenes as all pre CD based games often did. Dark Souls is a recent example of a modern game that does this.

I’ll discuss Live Action first, since with the continuing growth of graphics, cutscenes being filmed with a physical cast is becoming a rarity. Unlike the other types of

A screenshot from the FMV game Night Trap.

cutscenes, the live action ones are just recorded film. In that sense, they are not that much different from any film or TV show you watch. On the production side, it has little to do with the development of the game on the actual ‘game’ part of the production. During the early days of using disk technology (CD-ROM for example) in the 16bit consoles like the Mega Drive/Genesis Sega CD, there was a boom in this type of cutscene. Sometimes full games were made from these cutscenes, like the infamous Night Trap.

Live action cutscenes are generally known for being filmed on a low budget, with the dialogue and quality of acting often being rather poor. However some games have become well known for this B-movie like quality. The original Resident Evil for example, used live action film in its opening. The B-movie quality of the game has gone on to become a well regarded aspect within the Resident Evil fan base. Also given that Resident Evil is supposed to be a horror series (or was depending on your opinion) these scenes were a perfect fit for the game.

The ending of the original Resident Evil on the PSX.

Naturally there are examples of live action cutscenes used very well within games as well, with perhaps the Wing Commander and Command and Conquer series being the most well known examples. While the production values of these games were no different, their overall quality was better due to better direction and acting. Command and Conquer capitalised on them over time, taking a more comedic approach as the series continued.

Tim Curry in C&C Red Alert 3, where overacting is part of the fun.

A Pre-Rendered cutscene is a video that plays between bouts of game play that’s on the game disk in video format. It’s not interactive, as the game’s console/PC doesn’t actually generate anything, they just play the file. Rendering is the process of making videos from a PC, frame by frame, hence the name pre-rendered. I generally group pre-rendered cutscenes into two subtypes; the ones that are designed to look amazing, with graphical quality that is leaps and bounds ahead of the game’s in-game graphics, and the cutscenes made to mimic the look of the game in every way, so that it’s not apparent that the game is playing a cutscene, hopefully going unnoticed by the gamer.

A high quality cutscene from Final Fantasy X.

It’s actually easy to recognise most types of cutscenes if you know what you’re looking for. High quality ones like you might see in a Final Fantasy game are obvious. These generally look a lot more advanced in graphical quality, again due to the scene being a video and not actually being created by the games console. The use of videos started when games switched to using CD ROMs. Having a much higher storage capacity than cartridge based consoles (a cartridge normally being less than 20mb compared to a CD ROM’s 700mb), and looking at the amount of videos on the Playstation Final Fantasy games, you can see why they hit up to 4 disks in size.

There are more benefits to using videos for the scenes. One regularly used tactic is getting a different team to make them. They can be developed by a different department or even a different company that use an array of software tools, which won’t work in a game. This allows the use of the most modern computer animation technique and software to make an as technically impressive video as required. For many games, these videos might be used for an opening and closing cutscene, with everything else happening real time (Kingdom Hearts is a good example of this). In Mass Effect 2, the original CGI trailer was made by a different company, as well as the operation montage of Shepard’s body being rebuilt on the surgery table. In my Top 10 Video Game Cutscenes list I mentioned Onimusha 3; it’s opening cutscene is one of the most advanced and costly cutscenes ever made, and is a mini movie in itself.

Kingdom Hearts Re: Chain of Memories gameplay

Now on the other side of the equation, let’s compare this to cutscenes created with the real time engine. Which straight away brings up the question, why not just let them play out in game? Well there are a number of reasons which I’ll expand on a little bit, but generally when this method is used properly, you should never actually notice that you are viewing a video rather than the scene taking place in real time. One of bigger games to use these types of cutscenes would be Resident Evil 4, and in the case of this game, leads to some quite awful continuity moments–not in a plot sense, but more in an aesthetic point of view.

From the opening cinematic in Kingdom Hearts 3D.

Now a pre-rendered cutscene can be very obvious, or cleverly hidden, depending on how the game was developed. For example a video will load almost instantly, whereas a real time scene will have to load first (though this is not always the case, as data can be loaded ahead of time; heavily scripted games tend to do this). There can be downsides to using them, especially when characters have extra costumes. The costume might revert back to the default during a particular scene (like the PS2 Resident Evil 4 port). Perhaps the biggest use of these can be found in ports to other consoles. When a game is ported to another system after its original release, and the console is technically inferior to the one the game was developed on, cuts and changes might have to be made to make some scenes work. Making it as a video is a less memory intensive way of accomplishing the scene.

Resident Evil 4, with Leon in his default clothing.

This is why I used Resident Evil 4 as an example before. Originally being developed on the Gamecube, it was eventually ported to the PS2. However the PS2 was technically inferior compared to the newer Gamecube. So cut scenes were rendered out as videos where they were actually real time on the Gamecube version. This lead to odd changes when you’d be wearing a secret costume for example, and you jump out a window and see Leon in his default costume until he hits the floor and you start playing again. Other examples would be multi-platform games on the Xbox 360 and PS3. Due to the space limitations of DVDs vs Blu-Ray disks, videos might be a lesser resolution to save space on the Xbox 360 (Blu-Ray disks have many more times the capacity of DVD’s).

Resident Evil 4, with Leon in the Secret RPD costume.

I’ll explain what I mean when I say rendering on the console. Firstly you’re not limited by the processing power of a game’s console. Developers are free to use as many effects or have as many characters on screen as required by the scene. Also, changes are a lot easier to make. For example, making a change to the model’s texture to shoot a cut on them, the game would need to have that extra texture included on the disk, and be programmed to swap that texture when required, which might not be worth the trouble for a few seconds of the game. Another example would be if a model in-game looks odd when moving, you can’t just change the model in game (there would again have to be two models instead, which adds more data to the disk). For a video however, like in any animated film, you can change a scene as much as you need to, to get the shot you need. This leads us into the final area of cutscenes.

Like any other cutscene, there’s no limit on its length. However if a scene was to be about five seconds long, you’d probably find that it would be done in-game, like someone walking through a door. Whether to do a cutscene in-game will depend on a number of factors, such as what is supposed to happen in the scene; combined with what the console is able to do. Every company that creates games will have a list of rules they have to work to when creating a game; consoles the game will be on, development tools, model limitations etc. There’s an allotted amount of memory which counts for disk space, console memory, and bone and polygon counts on models, and development has to keep on budget. There will always be something the game engine can’t support or that simply won’t work on a console (naturally as technology improves, the amount that a console can’t do decreases). These all have to be accounted for and worked around, which can lead to some scenes being pre-rendered instead.

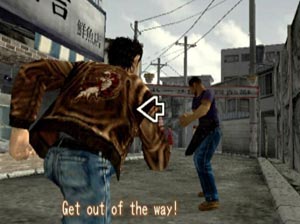

An example of a QTE from Shenmue

Real-time cutscenes have become more popular over the last generation because they allow for interactivity. Games like Uncharted have done incredible real time cutscenes that transition beautifully. Also Quick Time Events (QTE) have become very popular since cutscenes became real time. Originally débuted in the Dreamcast game Shenmue, QTE’s work like family trees in how they function, with two potential scenes playing out based on whether a button is pressed in a certain time limit or not. This system is how the whole experience during Heavy Rain plays. The complexity of what can be done has evolved greatly over the last two console generations. This current generation has allowed us to create games that look more realistic than ever. There are now fewer reasons to cut into pre-rendered scenes to show a big event, as developers have graphics that are able to create more lifelike games. It is slowly becoming a case of real time cutscenes being used because they provide interactivity, and pre-rendered scenes being used for special scenes, or when something still can’t be achieved technically in the game engine.

Heavy Rain gameplay.

In Jak 2: Renegade‘s ending cutscene, the PS2 had to be carefully managed due to the high number of characters present in the scene. All the game’s major characters were present in one place, and the amount the PS2 system had to render was causing performance issues, since the hardware could not sustain having so many characters on screen at once. The scenes had to set up so that they would show a certain number of people on screen at a time to stop the frame rate from dropping. This would have been a good case for making the scene pre-rendered, however creating a long scene as a video uses up a lot more disk space. (Today Microsoft adds a charge to developers for having games span multiple disks). Often it’s easier to work around the problem in a real time cutscene when all the texture, model and game data for that cutscene already exists on the disk. All that’s added is animation, voice and programming data to play the scene out, as opposed to a data heavy video.

An example of a cutscene from Jak 2: Renegade

Let’s come back to Mass Effect 2 for a bit, as this helps illustrate my point. The opening surgery cutscene had a lot of parts that would never be seen in-game. So having it pre rendered made sense, and allows the quality to be very high, making it stand out.

From Mass Effect 2's haunting opening cinematic.

(Also the promotional video the company had previously done, had been very well received, so Bioware had them do something else for the game)

The previous Mass Effect had also used pre-rendered shots for the Prothean visions to show off the eerie details of flesh mixed with circuitry, while providing something of an out of body experience. This holds true for the surgery cinematic in Mass Effect 2–it’s the only time you’re not technically playing Shepard, providing another form of out of body experience.

As an example of good cutscenes, here is a collection of my favourite video game cutscenes. In the video, I also explain what I think makes each cutscene so great. Click here to see the video if you are reading this in an email or RSS feed.

That’s it for my little (or maybe not so little) look into the world of cutscenes. I hope it helps you understand how different cutscenes work, and why certain design choices are made. Of course, every company works differently. They all develop their own custom tools and techniques, so what might be an issue for one company’s game, might not be for another. So if you want to learn more about a specific game, then look up the developers for media on their development process. EPIC’s and Naughty Dog’s (Gears of War and Uncharted) developers have all sorts of videos around the net on how they produced each of their games. Lots of games also now include special features that show off the development process, so look those up too and see how your favourite scene of a game might have been created!

Uncharted 2

If you have any questions about video game cutscenes, or you would like to share your own viewpoints on cutscenes in the gaming industry, please post them in the comments below. We’d also love to hear what your favourite video game cutscenes are.

Written by

David ‘Ryatta’ Wyatt

David is a Technical Animator, and has worked on creating Xbox 360 and IPad games. He also writes reviews and articles for inMotion Gaming and on his blog.

PS: If you enjoyed this article, help spread the word by clicking the “Like”, “Tweet”, “+1” buttons, or sharing it using the share icons below. Want to read more articles like this? Subscribe to iMG, and get our articles and reviews directly to your inbox or RSS reader.

Very interesting article! It’s crazy how quickly video games have evolved, huh?

It seems like the evolution happened so quickly, though there’s not been much this generation and console cycles are getting longer